Anatomy Education Is More Than Just Memorization

by Robert Tallitsch, PhD | February 3, 2020

Throughout my 43 years of teaching anatomy, I came to understand many things about student learning. One of the most important things I learned was that many students didn't understand how to really learn anatomy. If I had to take a guess, I would say many of your students don't either. One large misconception in the eye's of anatomy students is that our courses are all about memorization and “spitting back” information. Once you understand this, you will realize that these students truly need your help in order to succeed in these courses and in the workplace.

To help these students avoid or eliminate this misconception, I would work with my students to do at least three things:

- Discover anatomical trends.

- Look for anatomical relationships (i.e. structure “A” lies deep to what structure(s), superficial to what structure(s), and/or medial or lateral to what structures?).

- Learn how to apply the information that they have learned in order to solve complex clinical problems.

How would I get students to think about these questions? By asking students questions and increasing student participation in class — a recurring trend in my blog series. By asking questions, I would get my students to notice the trends rather than me having to identify them. Granted, student involvement can’t solve all of your lecture or laboratory problems, but it sure can (and does) solve or prevent many.

So…let’s look at the musculoskeletal anatomy of the anterior forearm — a topic that always seemed to frighten students because of its perceived complexity and vast amount of memorization. However, once students discover, learn and understand the many trends and relationships that this part of the body demonstrates, they quickly realize that it isn’t as hard as they initially thought.

Here are a few examples of anatomical trends that you should encouage your students to recognize and understand.

- First, the anterior musculature of the forearm is subdivided, from superficial to deep, into compartments. The superficial muscles have at least one origin on the medical epicondyle of the humerus. As you move deeper, the origins move to the radius and/or ulna, as well as other structures of the forearm.

- Second, as the bodies of the muscles are found more laterally within the forearm their insertions move either lateral to medial or medial to lateral, depending on the compartment.

- Third, except for one of the muscles of the forearm, all are innervated by the median nerve. The exceptions are the flexor carpi ulnaris (innervated by the ulnar nerve) and the flexor digitorum profundus (innervated by the median and ulnar nerve).

- Finally, all muscles of the forearm receive their blood supply from some branch of either the radial or ulnar artery.

Let’s take a look at these trends. First let’s look at the trends that emerge regarding the origins of these muscles. Throughout my teaching I found that students understood this trend more easily if the anterior forearm was divided into three compartments: superficial, intermediate and deep.

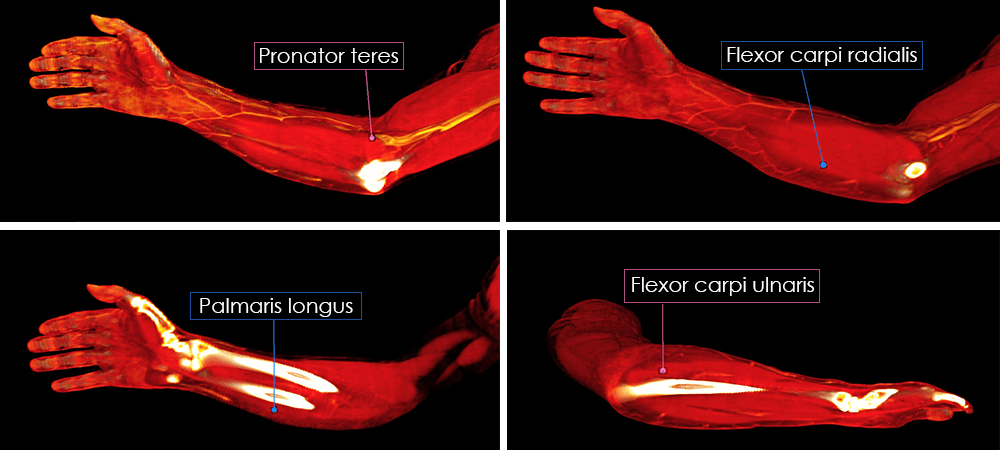

There are four superficial muscles: pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, and flexor carpi ulnaris. All four originate on the medial epicondyle of the humerus. The most medial (pronator teres) and lateral (flexor carpi ulnaris) muscles also have one or more origins on the ulna. Note the trend? The palmaris longus is the only muscle in the intermediate compartment. It originates from the medial epicondyle of the humerus and the radius and ulna. See the trend here? This is a deeper muscle, and so it has an origin on the radius and/or ulna. The deep compartment has three muscles: flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicus longus, and pronator quadratus. Two (flexor digitorum profundus and pronator quadratus) have an origin on the ulna, and the flexor pollicus longus has an origin on the radius. In addition the two muscles with the word “flexor” in their name also originate from the interosseous membrane of the forearm. None have an origin on the humerus. Again, see the trends?

Now let’s look for trends in the insertions of these muscles.

For the superficial compartment, here are the insertions for the four muscles in that compartment. Note how all of the insertions move from lateral to medial.

- Pronator teres = radius

- Flexor carpi radialis = 2nd and 3rd metacarpals

- Palmaris longus = flexor retinaculum and palmar aponeuroses

- Flexor carpi ulnaris = 5th metacarpal, pisiform and hamate

The flexor digitorum superficialis is the only muscle of the intermediate compartment. This muscle inserts onto the phalanges of digits 2 through 5 — also lateral to medial.

For the muscles in the deep compartment note how these insertions move from medial to lateral — opposite that of the superficial and intermediate layers.

- Flexor digitorum profundus = distal phalanx of digits 2 through 5

- Flexor pollicus longus = distal phalanx of the thumb

- Pronator quadratus = radius

As I mentioned in my blog about Tommy John surgery, I visited a colleague this fall and worked with him to increase student participation in his class. We talked about this example after that class. His question to me about: “How do you get the students to see these trends?” I told him to assign the appropriate reading so the students have it completed before it is covered in class. Make sure that you tell them to look for and write down any trends that they see as they read the information. Let them work in groups if they want, but they must write down their findings and bring them to class. Then, in class, talk about any and all observed trends. If the students see the trends themselves rather than you telling them, the information will stick with them longer, and they will understand it better. This is yet another example of how student involvement facilitates learning.