Anatomy and Pathophysiology of Kidney Stones

by Robert Tallitsch, PhD | August 10, 2021

.jpg)

Simplified explanation of Kidney Stones including symptoms, causes, treatments, and a patient example!

Although there are still some that do not, every anatomy educator should be incorporating real-world connections into anatomy curricula. Many of us struggle with classroom engagement and student retention of course material. Integrating real-world connections into our anatomy curriculum helps students realize that what they are learning about is useful beyond the classroom and workplace. Real world connections help spark student curiosity and create engaging group discussions, which in turn, reels in students who the topic may not have resonated with initially. After I started utilizing real-world connections in my classroom, I cannot recall the number of times where my entire class session would be spent answering student questions in-line with our course material. Those are the moments we work timelessly for as educators; those are the classes we remember. And just like us, our students remember those classes and topics discussed as well.

Years ago one of my student’s asked me about kidney stones (clinically referred to as urolithiasis or nephrolithiasis) and the intense pain and treatment that his father underwent. As it turns out, kidney stones are fairly common so this was a topic that students connected with one that, from that day moving forward, I always tried to incorporate into anatomical discussions. So…let’s think about what kidney stones are, how do they form, why do they cause such pain, and how is someone treated for this urinary problem?

What Are Kidney Stones and Why Are They So Painful?

Kidney stones are the result of supersaturation of urinary inorganic and organic salts, combined with proteins. These supersaturated salts precipitate within the kidney. One of the major causes of this supersaturation is reduced urinary volume. Other causes range from diet to kidney infection. The most common kidney stones are composed of precipitated calcium salts, most commonly calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate. Other types of kidney stones are formed from uric acid, cystine or are the result of a kidney infection altering the chemistry of the kidney, thereby causing the formation of one or more kidney stones.

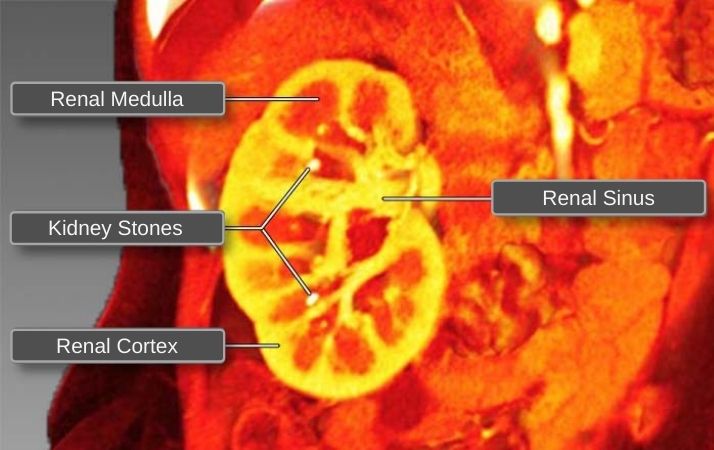

Researchers and clinicians do not agree on whether or not a small kidney stone within the renal pelvis causes mild back pain. However, a kidney stone that moves into the ureter produces severe pain in the side and back, typically inferior to the ribs. This pain often radiates to the lower regions of the abdomen and into the groin, typically coming in waves and fluctuating in intensity. Pain from kidney stones is often so intense that it causes nausea and vomiting. (Pain resulting from a kidney stone is often described as some of the most intense pain caused by a non-life threatening condition.) Diagnosis for a kidney stone typically includes a urinalysis to determine whether or not blood is present in the patient’s urine, as well as a CT scan. The CT scan determines the location or locations of the stones, the number of stones, and their approximate size, as shown below.

How Do We Treat Kidney Stones?

Although treatment for kidney stones depends on the recommendation of the physician, typical treatments for renal (kidney stones located within the renal pelvis) and ureteral (kidney stones located within the ureter) will vary. If the physician determines that the kidney stones are quite small, the patient may be treated for the pain and told to filter their urine in order to determine if and when the stone is passed.

Renal stones smaller than 2 cm, or ureteral stones smaller than 1 cm, may be treated by extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. This treatment involves the administration of a series of shock waves generated by a machine termed a lithotripter. The shock waves are focused at the kidney stone(s) by x-ray. The shock waves are transmitted through the body, with the goal of breaking the stone(s) into smaller pieces that may be passed naturally and with little pain.

Alternatively, ureteral and renal stones smaller than 2 cm may be treated by ureterorenoscopy. A ureterorenoscope is a flexible fiberoptic endoscope that is inserted into the urethra, passed through the bladder and into the ureter. Depending on the location of the stone the endoscope may be passed up into the renal pelvis of the kidney. The stones are either removed with a grasping device or the stone is fragmented with a laser and then removed with a grasping device.

If the ureter is inflamed due to irritation from the kidney stones a stent is inserted through the urethra and bladder and up into the ureter, often extending into the renal pelvis. This soft hollow tube allows urine to pass through the ureter into the bladder, and is typically left within the ureter until the swelling goes down, which usually takes 7 to 10 days.

Kidney Stone Prevention

Kidney Stone Prevention

The best way to prevent kidney stones is to stay well hydrated, which will increase urine flow and, hopefully, reduce the probability of a kidney stone forming. And, speaking from experience, a kidney stone is nothing that you want to endure!

Additional Articles: